- The fact that inflation remained relatively stable suggests that the recent rise in interest rates is not likely to be a multi-year event.

- If we enter another economic slowdown, this could mean that a new recession may be longer and more severe than it would otherwise be.

- It is important to watch whether interest rates on longer-term bonds will stabilize near historical levels of around 2% over the inflation rate or whether rates will move higher on concerns for longer-term inflation.

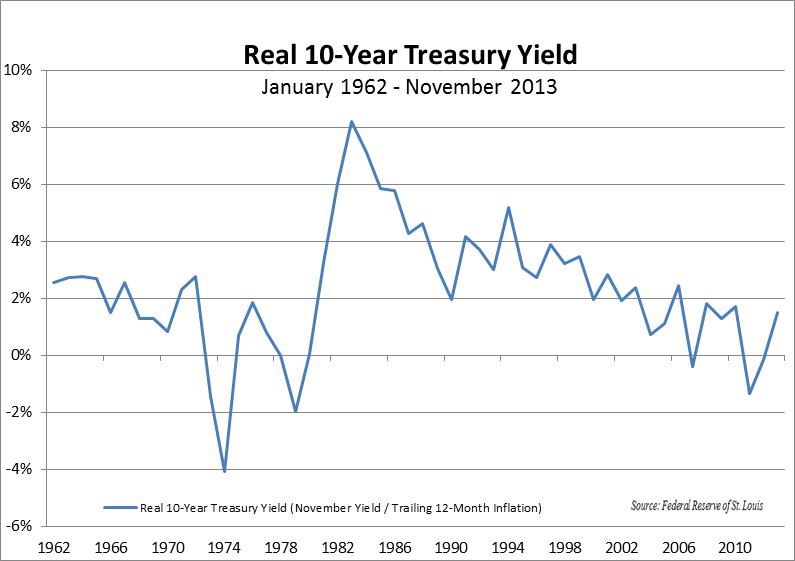

In my Market Insights column of December 2012 I discussed the two most likely paths that interest rates may take in the future. The first possible option would be following the path of Japan who since the late 1990’s has stayed below 2% on longer-term government bonds. The second possibility was to follow the path of domestic interest rates during the mid-to-late 1970’s. During this time extensive stimulus from the Federal Reserve (Fed) after the recession of 1973-74 (the deepest recession since the end of World War II prior to the recession of 2007-2008) led to a significant rise in interest rates culminating with rates moving to levels upwards of 10% in the early 1980’s.

If we take a look at what has transpired in the year since that commentary was written, we are following the path of the 1970’s more closely than the Japanese scenario. 2013 was the worst performing year for bonds since 1994 as measured by the performance of the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index. Longer-term treasury bonds performed even worse, with a decline of over 13%1 for the year.

In looking back at what transpired in 2013, and what we are likely to see in the bond market in 2014, there are some important considerations. First, while it is true that interest rates rose, inflation remained at levels similar to the past couple of years. This is important because steadily rising inflation would likely be a multi-year negative for bonds. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) measure of inflation advanced 1.7% for 2012 and is up 1.2% for the 12 months ending November 2013. The fact that inflation remained relatively stable suggests that the recent rise in interest rates is not likely to be a multi-year event.

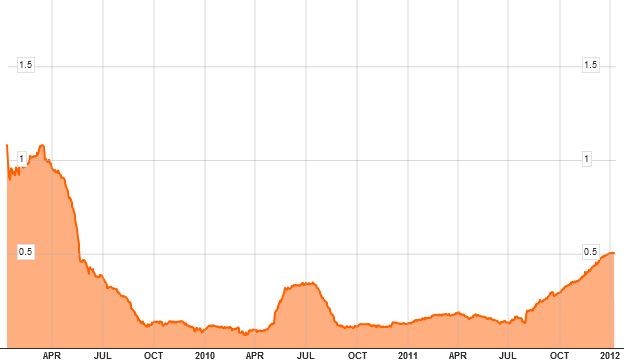

A second important factor is the current level of interest rates relative to inflation. For this evaluation I feel that it is more important to look at rates that are determined more by the markets than by Federal Reserve policy, so we will look at the rates on 10-year government bonds rather than on Treasury Bills or similar short-term instruments. In 2011 and 2012 when the yields on 10-year government bonds dropped down into the sub 2% range, bond yields were below the historical level of inflation, historically that has not happened very often, and when it has, it has not been sustained for an extended period of time. As the chart below shows, since the early 1960’s there have been four cases where interest rates dropped below the current level of inflation, but none were able to be sustained for multiple years.

An additional important consideration is the desire of the Fed to see us return to a more normal interest rate environment. Although historically low interest rates do help to stimulate the economy by reducing borrowing costs, there are potentially serious consequences to this strategy. Leaving interest rates at extremely low levels would mean that the Federal Reserve has little room to use rate cuts as a tool for stimulating the economy. If we enter another economic slowdown, this could mean that a new recession may be longer and more severe than it would otherwise be. Think of it like when you have a virus and go the doctor and the doctor gives you some medicine to get rid of the virus. If the first medicine provided does not work, the doctor switches you to another medicine that is stronger and should work better, however, it does not get rid of the virus either, so the doctor goes to a third and final standard medicine for dealing with the virus. At this point, you really need the medicine to work, because you don’t want to be out of options or to rely on experimental medicine to get rid of the virus.

There is also the potential for low interest rates and programs like Quantitative Easing, which pump money into the economy through bond purchases to build an inflationary momentum which may become difficult to contain. This was one of the adverse side effects of Federal Reserve policy after the Oil Shock and Recession of 1973-74, which can be seen in the chart shown above, and also had periods where bond yields dropped below the level of inflation to an even greater extent than what we have seen over the past couple of years. In the case of the 1970’s, as inflationary pressures began to pick up in the years following the recession the Fed was slow to increase interest rates and inflation began to get out of control which led to double digit interest rates and back-to-back recessions in the early 1980’s as the interest rates were pushed to historic highs in an effort to break the back of inflation.

In summary, The fact that 2013 was not a good year for bonds does not automatically mean that we are going down a path that is similar to the 1970’s, although it does make that outcome look somewhat more likely than following the path of Japan with sub 2% interest rates. What is important to watch is whether interest rates on longer-term bonds will stabilize near historical levels of around 2% over the inflation rate, or whether rates will move higher on concerns for longer-term inflation. In addition, it will be important to see how the economy reacts to the increase in interest rates, think of it as a two-step process with the longer-term interest rates, which are typically driven by market forces, moving higher and the Federal Reserve closely monitoring the impact to determine if the economy is strong enough to withstand increasing short-term interest rates, which are driven by Federal Reserve policy back to normal levels. Getting back to normal interest rate levels relative to inflation for both short-term and long-term bonds while maintaining sustainable economic growth is in the long-term best interest of the economy. We are beginning to move in that direction and as the year unfolds we should get a much clearer picture of whether we are finally able to get back to a “normal” economic recovery. It will be interesting to watch the developments during the year and adjust the investment portfolios as needed.

Happy 2014!

Michael Ball

Lead Portfolio Manager

Sources: (1) www.yahoofinance.com;NYSE-Arca

Disclosure: Opinions expressed are not meant to provide legal, tax, or other professional advice or recommendations. All information has been prepared solely for informational purposes, and is not an offer to buy or sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, any securities or instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. All opinions and views constitute our judgment as of the date of writing and are subject to change at any time without notice. Investors should consider the investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses of the underlying funds that make up the model portfolios carefully before investing. The ADV Part II document should be read carefully before investing. Please contact a licensed advisor working with Weatherstone to obtain a current copy. The Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate Bond Index is a market capitalization index consisting of treasury securities, mortgage-backed securities, foreign bonds, government agency bonds and corporate bonds. The bonds represented are medium term with an average maturity of about 4.57 years. The index represents about 8,200 fixed-income securities. Weatherstone Capital Management is an SEC Registered Investment Advisor with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Weatherstone Capital Management is not affiliated with any broker/dealer, and works with several broker/dealers to distribute its products and services. Past performance does not guarantee future results.